Basics of Amplitude Modulation, Part II

By Ed Montgomery

This is the second part in a series about the basics of amplitude modulation. For continuing education credit, see the information at the end of the article.

Amplitude modulation is a simple, efficient method for transmitting information. The original idea for creating a radio signal goes back to James Clerk-Maxwell, an English physicist who theorized the existence of electro-magnetic energy in 1873. His theories were proven by Heinrich Hertz, who actually generated and received radio waves in his laboratory in 1888. Hertz did not follow up his work with any practical applications.

|

Read

Other Parts in this Series:

|

|

It was Guglielmo Marconi who found the practical application for the "wireless telegraph." Marconi implemented a system of radio communications between ships and coastal stations he had established on land. Most of these systems employed an alternator similar to the one in an automobile to create a radio signal.

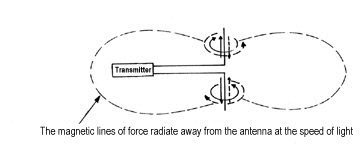

The radio wave is the product of an electric current flowing through an unterminated wire or antenna. As the alternating current flows to the end of the wire and then back, a magnetic field is created perpendicular to the current flow. If the wire is spread apart as illustrated in Figure 1 (below), the magnetic field will radiate away from the transmission line.

Spreading

the wires apart creates an antenna. The radio wave is moving away from

the antenna at the speed of light. Originally this magnetic field would

be intercepted by the receiver antenna, and through electro-magnetic induction,

produce a small current that would actuate a relay creating a clicking

sound. Morse Code was sent this way.

Spreading

the wires apart creates an antenna. The radio wave is moving away from

the antenna at the speed of light. Originally this magnetic field would

be intercepted by the receiver antenna, and through electro-magnetic induction,

produce a small current that would actuate a relay creating a clicking

sound. Morse Code was sent this way.

But some people wanted to do more than just transmit code. One could say that the frequency that was transmitted with code was the carrier. To transmit voice, more than the carrier had to be sent.

It was discovered that if audio signals were converted to electric current variations, through a microphone, these signals could be added to the radio frequency and decoded in a receiver. Initially these audio signals were capacitively or inductively coupled to the radio frequency. Pioneers like Reginald Fessenden and Lee DeForest demonstrated audio transmissions around the United States and Europe.

However, it was another individual, more closely associated with FM, who improved amplitude modulation and made it practical for broadcasting. Edwin Howard Armstrong invented the principle of regeneration or oscillation. This allowed the alternator to be retired. The totally electronic transmitter was at hand. Armstrong also invented the superheterodyne receiver, making radio reception simple and reliable.

The carrier

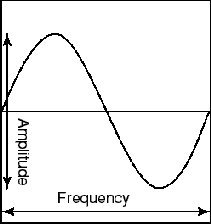

Amplitude modulation operates on a specific frequency known as a carrier. This signal never changes in power. The operating power of a broadcasting station is the carrier power. The radio signal is generated in the form of a sine wave. Figure 2 (below, left) depicts its wavelength and amplitude characteristics. The number of wavelengths occurring in one second is the wave’s frequency, measured in cycles per second, or Hertz.

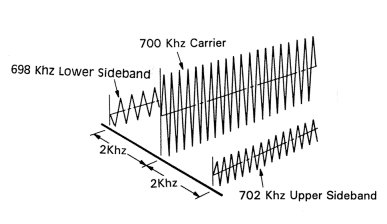

The audio signal is added to the carrier frequency creating modulation. For instance, if the carrier frequency is 700 kHz, the radio signal, or carrier, is creating magnetic fields that are radiating off the antenna at 700,000 times per second. If audio is applied to this carrier, the sum and difference frequencies also will be transmitted. If an audio tone of 2,000 cycles is applied to the carrier, the following frequencies will be present:

Audio Frequency: 2,000 Hz

Carrier Frequency: 700,000 Hz

Sum Frequency: 702,000 Hz

Difference Frequency: 698,000 Hz

The antenna will accept the frequencies that are most closely related to the carrier: 698 kHz, 700 kHz and 702 kHz. The 698 kHz and 702 kHz are sidebands. The difference between the carrier and sideband frequencies is the audio frequency. It is duplicated above and below the carrier.

Figure 3 (above, right) depicts the sidebands and the carrier. The amplitude of the sideband determines the loudness of the signal while varying frequencies in the sideband represent the audio information. For years, radios used a diode or envelope detector to extract the audio from the radio signal and amplify it.

Much of the problem with AM broadcast today is not within the transmission of the signal but in its reception. Most electro-magnetic noise, from lightning, motors, computers, etc., is an amplitude function. Because the AM receiver is detecting amplitude variations, it receives the desired signal along with any other electro-magnetic noise in the vicinity.

Remember the radio signal is very weak. Signals from computers, telephone systems, appliances, and so many other local sources are much stronger. The receiver picks up everything surrounding the carrier and amplifies it, often producing a lot of noise.

Over the past 30 years, receiver manufacturers have tried to reduce noise by narrowing the frequency bandwidth of the tuner.

AM transmits a frequency response that is very close to human hearing. It is flat out to 7,500 Hz and beyond. However, audio is varying constantly, allowing noise to get in where low levels of radio signal are present. The receiver manufactures decided to cut the audio bandwidth to 2,500 to 3,000 Hz. This reduces fidelity.

There are other methods available to reduce noise in AM while keeping audio fidelity high. One is to replace the envelope detector with a synchronous detector. That was once an expensive addition, but now simply requires a microprocessor. Receivers with AM stereo capability use them with good results. Many automobiles have them. They do not eliminate noise, but they reduce it.

Denon has made a receiver sold by the NAB that has a "smart filter" that will eliminate a lot of noise. However, few consumer stereo manufacturers have chosen to add this feature in their AM receivers. Even the ingenious Bose wave radio, which uses a synchronous-type of detection circuit, has no provision for decoding a stereo signal.

We will continue the discussion in our next part.

You can receive continuing education credit from Northern Virginia Community College as part of this series. The course fee is $30, payable to the college. For a faxed copy of the registration form, send e-mail to radioworld@imaspub.com or call (703) 998-7600, ext. 117

Ed Montgomery is the video technology and communications lab director at Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology, Fairfax County, Va. He has worked as a broadcast engineer and college-level instructor. Reach him at emontgom@lan.tjhsst.edu